Understanding Calculated Columns & Fields

Calculated columns and calculated fields are actually quite different despite initial similarities. Here we will explore the differences of columns of fields, while gaining DAX concepts and syntax.Calculated Columns

Before in P2.2, we touched upon the notion of creating a calculated column and a calculated field. By clicking the Add Column button on the Design tab, we can create a calculated column in PowerPivot. It is versatile in PivotTables; also the DAX expression for the column applies to the current row of the table. When we reference a column, it returns the value of that particular column in that specific row. |

| Fig. 1: Add Column Button |

There are DAX functions which aggregate the values of a column for a whole table. To evaluate a subset of rows, we use DAX to specify a range of rows or a single value from another row and operate on that subset table. Essentially we can restrict rows and apply filters so the desired rows are selected for computation.

Calculated Fields

Now for something a little different. While calculated fields use the same DAX syntax as calculated columns, calculated fields evaluate the expression at the context of the cell of the PivotTable, not at the row level of the PowerPivot table like a calculated column. |

| Fig. 2: Calculated Fields Button |

So if we used the regular formula to calculate a field, we could get the following error:

|

| Fig. 3: Calculated Field Error Using the Same DAX Expression as Calculating a Column |

The correct method was to type in the sum of each:

=SUM(Sales[GrossMargin]) / SUM(Sales[SalesAmount])

and then divide them, as shown in Figure 4.

|

| Fig. 4: Using the SUM for the Correct Calculated GrossMarginPct Field (See: No Errors!) |

|

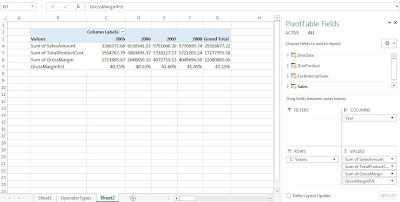

| Fig. 5: PivotTable with GrossMarginPct |

When to Use Calculated Columns and Measures (Fields)

So when do we use a calculated column and in other cases, a calculated field (or measure)? (When do we get to eat Jell-O?) In most situations, it would depend on the computation of choice. For example, there are several situations to use calculated columns:- When we want to evaluate an expression which is confined to the current row,

- The results will be displayed in the columns or rows of the PivotTable, and not the values,

- Or when we categorize text or numbers (categorical variables)

Situations where we would use calculated fields occur when we would like to display the results in the PivotTable Values section. Each cell in the Values section will change based on the context of the rows and columns in the PivotTable selections. If we changed the rows in Figure 5 to include the ModelName, then the calculationed field would reflect the change, and show the GrossMarginPct stratified by ModelName (Figure 6).

|

| Fig. 6: PivotTable with ModelName Stratifying the Calculated Field |

Cross-Referencing

We can use calculated columns in our DAX expressions when creating calculated fields. Also, the reverse can be done as well. However counter-intuitive, a calculated column can reference calculated fields, and this confines the calculated field to the context of the current row. Therefore, the calculated field transforms into a calculated column, and will not be influenced by user changes in context on the PivotTable.Here we have explored the similarities and (for the most part) differences between calculated columns and fields through DAX. Understanding these concepts are important in becoming proficient at DAX, as well being able to manipulate data efficiently.

Thanks for reading,

Wayne